To reach the future, you make a sharp turn off Ft. Lauderdale's State Road 84 where it crosses the New River's South Fork onto a bumpy side road and, more likely than not, you end up hubcap deep in old tar at the back of a paving company. You've taken the wrong fork; backtrack and continue until you reach the docks of Marina 84 - home of Schoell Marine and Nautical Engineering - the company that builds Infinity Yachts. From all appearances, you're at a conventional dealership. "Trojan" is emblazoned above the showroom. But, once you've been given a tour of the place by the owner Harry Schoell, you begin to wonder if you haven't reached the North Pole - home of Santa's workshop - despite the 93-degree heat.

Harry himself looks like one of Santa's helpers - short, jolly, balding with a red beard, brimming with enthusiasm. He is a Santa figure, busily directing a close-knit staff in the arcane art of breakthrough boat building that Harry is convinced will be the greatest gift to the boating public since oarlocks. And, like Santa, Harry's goal is giving people what they want: "Hey," he says, "boats are toys! Unless your building a straight commercial vessel, they're all toys. So why not have the most fun with the most toy? We're talking about self-gratification." We sure are... Harry's.

The workshop - a large shed and the raison d'etre for the rest of the complex - is behind the main building where Harry keeps the dealership and the drawing board that he works at about 28 hours a day. The two buildings are separated by a short, flooded road with ruts undoubtedly caused by Harry's trips between them. Approaching the shed evokes the sensation of going to check out a giant still. Surely, the rusticity belies the future shock within. But no, except for a huge hull (Hey? Where's the mold?), things look timeworn - almost downright archaic. Instead of space-age computerized construction, we have a few laid-back guys doing everything by hand. "This has never been done before," repeats Harry as the ubiquitous fiberglass sticks to his shoes and he reels off facts and figures relating to the harmonics of a fiberglass prop. "We're improving the state of the art."

There is, however, something about the whole operation that makes you doubt that that Harry can accomplish a tenth of what he intends. On the other hand, if you had to bet on which designer/builder in the country is currently doing the most important work in terms of the future of boatbuilding, you'd be smart to put your money on Harry.

Certainly, no other 41-year-old mortal has packed as much boat building into his waking hours. Ask Harry how it was growing up - would he rather play ball after school or build a boat?

"Oh, I'd go out and build a boat." No hesitation.

"You'd go out and build a boat?"

"Oh, sure." As if everyone would have. "I'd stay up all night - drawin' em, makin' models, buildin' em. Made a lot of models. You know - first I'd try this out and then I'd try that."

Born in Miami in 1942, Harry got the boat bug from his father, who "always had a boat," and who sold his aluminum and bronze foundry in the mid-50's and began building plywood boats. "When I was a little kid, I was always in the backyard building a boat out of something. His early vessels were fashioned from packing crates. (Aha! a case of arrested panel development.) "One person paddled, one person bailed," says Harry, which cracks him up. By the time he was 12, he was building bona fide boats out of plywood and at 16 he was designing all the boats built by his father's firm. In high school (Miami Edison), he eschewed mechanical drawing for lofting (the rendering of shape and contour using imaginary lines); an exquisite handcrafted sailboat model won him a Ford Foundation prize.

"I planned to go to the University of Miami," explains Harry, " But I got involved full time in my father's boat-building business." Such unidirectional single mindedness is hard for many people with more scattered interests to understand. Yet it's the stuff that outstanding accomplishment is often based on. Harry and his father came up with the V-20 in 1960 - a design still being produced by Wellcraft. Harry built the plug by himself in a week. He was 18.

"We brought in a partner to finance the operation," says Harry, "I'd spent a lot of time learning how to build boats but not how to handle the financial end of the business. My father was the same way -- a fantastic engineer and mechanic, but the worst businessman I've ever seen. We did some very stupid things. We basically just handed over the business to another person. When it came to money, I said, 'Hey, I'm busy building boats -- that's my interest.' Our partner ended up with the business and we ended up out on the street."

Credit to Don Seith

How can Harry successfully oversee a dealership, a prototype and design shop and a boat building yard? "I'm a better businessman than I was 20 years ago," he chuckles. In fact, he's become acutely aware that having a good product is merely a beginning and that a brilliant concept without public acceptance is just another flop. "Promotion is everything," he says. "That's why the deep-V caught on like it did." Harry gives much of the credit for his own success with his patented DeltaConic hull to Trojan's President, Don Seith. "Seith sold everyone on the DeltaConic hull, but it had been around several years before Don got a hold of it. You can have the best invention in the world, but unless the public knows about it, it's just going to sit there and die." He gestured to a bundle of flat files against the wall -- obviously something of a graveyard. He also gives credit for his current work to staff engineer Mike Hodges and shop superintendent Jim Gardiner (both of whom are partners in Nautical Engineering).

In 1966, Harry founded Vega Boats and began building a little fiberglass 21-footer, but he sold the company within two years because he couldn't stand the monotony of mass production. He opened a prototype shop in Hallendale, Fl and began doing experimental designs. Don Aronow, who had just sold Formula to Thunderbird and was starting Donzi, had Harry design and build the plugs and molds for a half dozen boats, including a racer. Then Harry went to New York to build a 22-footer -- another mass production operation which he soon soured on. He returned to Hallendale and did the lines for the championship-winning Magnum 28 Aronow, who had by then sold to Donzi.

Always a Little Different

Even from his earliest designing days, Harry never felt that he was working 'within the tradition.' "No. Never. I didn't like that at all. Just like I didn't like production. I can design production lines and design all the systems, but I don't want to sit there and 'run' the systems -- it's too boring. My head would be off somewhere else." Which may account for Harry's occasional spaced-out grin. There is always something a little different about a Schoell design, he explains -- something from wherever it is his head goes when he examines the current state of anything. Take offshore racing boats for example:

"Hey, today's racing boats are just straight out-of-date. There hasn't been anything new since 1966. They're extruded, constant-section, 24-degree hulls with lean, narrow entries. There are other shapes that are far superior."

"Like what?'

"Like this..." From the clutter on his desk he plucks a wooden model that resembles a water bug - a cigar shape with four little pontoons. "This could win everything." Harry explains it with an any-idiot-can-see-it confidence and matter-of-fact tone that makes the water bug's victory a fait accompli. (Hey, does Ivory soap float?) "It has optimum angle of attack, optimum horsepower-to-weight ratio, excellent shock-absorbing qualities, low frontal area, high degree of stability, runs in rough water. You could make it an outboard, you could make it 60 feet long and put an engine on each sponson ... I'll put one together one of these days. I already have a plug." Wherever Harry's head goes, it isn't to Lilliput. He has a 100-footer in the works for Guy Couach and plans for fiberglass ships and tankers.

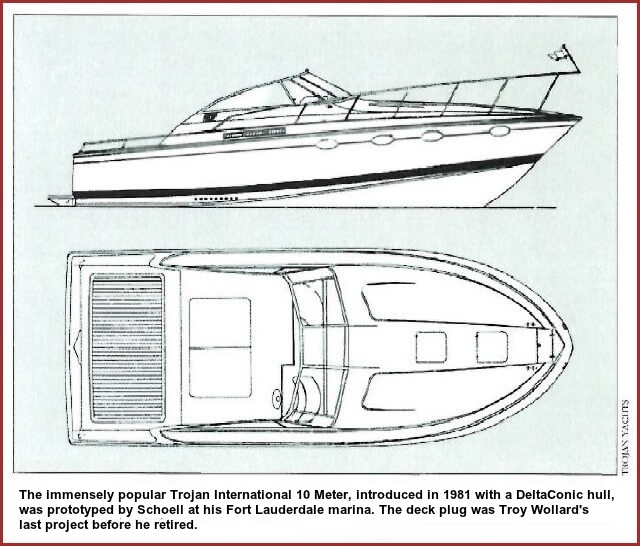

After designing the Magnum 28, Harry did work for SeaBird, Glastron, Hammond, IMP, Larson, North American. And then Trojan, where Don Seith embraced the DeltaConic concept and built Trojan's ever-expanding International line from Harry's design. What's so special about the DeltaConic? "It has a unique geometry that's predictable -- a geometry that takes the guesswork out of hull design." explains Harry. Then, ever mindful of the power of promotion, he adds, "The name is pretty good too." Indeed, despite Harry's patent, many designers see the DeltaConic as an old idea with a fancy new name. "I call my hulls

LepreConic" grins Shamrocks George Boynton.

Vision Incarnate

Whatever the verdict on the "revolutionary" DeltaConic hull, there's no denying that a couple of new wrinkles have been incorporated into 'Infinity' -- Harry's personal vision incarnate that he admits is a prototype -- an experiment in several respects but a boat that incorporates construction techniques and components that Harry believes are demonstrably superior to conventional ones.

The boat's most eye-catching features are it's modified A-frame mast - an arch that immediately prompted the nickname - "The McDonald's Boat" - and it's 14 foot wind generator prop (not in place in the accompanying photos). Yes, and the tender stores flush in the stern under the king-sized bed and the throttle controls are toggle switches and the gears and a host of other mechanical systems are push button controlled, and no screw heads or knobs or hinges show, and everything slides, and James Bond would feel right at home. (Harry already has an order for an Infinity with three Jacuzzis)

But the truly significant achievements embodied in the Infinity are the fact that it’s a 67-foot fiberglass boat and that it was constructed without a mold, and its 45lb weight to HP ratio that enables it to attain a speed of 24 knots with relatively tiny (671-T1) diesel engines. These are the "breakthroughs" that make Harry a good bet for the “designer of the future” award. Panel development -- the construction of carefully engineered hull sections that are bent into shape and bonded together in a cradle -- accounts for the absence of a mold. The boat's lightness is achieved using balsa core and unidirectional fiberglass with vinyl ester resin.

Harry is forever talking about "Tensils, flexurals, E-glass, S-glass, resin-to-glass ratios, inter-laminar shear, harmonics and pultrusions," but occasionally he descends to a level that makes sense to a layman: "Having built wooden boats gives you an edge in this business, because wood gives you a real sense for mechanical strength. You learn what it can and can't do. Wood has grain and fiberglass has grain too. If you understand how to take advantage of wood grain, it helps you understand how to use the grain in fiberglass in a particular application to derive the most strength from the material. If all you've ever done is build fiberglass boats, you tend to look at fiberglass as a material that has the same strength in all directions. In addition, there are different formulations and combinations of fiberglass that can be compared to using different types of wood." Therein lies the secret to much of Harry's success and the formula for much of the way Infinity was put together.

Harry is constantly experimenting. He gives the impression of looking at the world with an eye toward improving it with straight fibers and resin. How many hours has he lain awake pondering what else he could make out of fiberglass? On Infinity the rails, cleats, strainers, seacocks, struts, rudders, shafts and props are made of fiberglass. "Some plastics exceed metal in durability and strength" he notes.

Composites are where it's at

Obviously, Harry has no aesthetic reservations about abandoning traditional designs and materials. "That's already been done" is his way of acknowledging any classic vessel. "State of the art" is his stated goal in everything he undertakes, it is usually synonymous with "new and different." If your idea of a great boat is something created out of hardwoods and brass 'Infinity' may strike you as nothing more than an oddity. To those who understand the economics and material stress factors involved in both building and operating powerboats, however, there is no dismissing 'Infinity's' message: Technology will continue to lighten and synthesize pleasure boats to the point that if you believe in knocking on wood for luck you'd better bring along a toothpick. Natural materials in boats may soon be as scarce as wooden dashboards in cars. Composites are where it's at, and Harry Schoell has a jump on his colleagues -- probably due as much to his willingness to gamble as to his inventive nature.

It's a safe prediction that Harry will remain in the role of pioneer. With 'Infinity' still in the developmental stage, his enthusiasm was already spilling over to such projects as an underwater habitat, chemical tankers and water bikes; and a gleam came to his eye at the mention of carbon fibers.

If you meet Harry and compliment him on his work, you'll get an immediate feel for the man, since he'll undoubtedly reply, "I'm only just beginning."